Modern Date : November 18th

Ante Diem XIV Kalendas December

Fourteenth Day to the Kalends of December

This is one of the dies comitiales when committees of citizens could vote on political or criminal matters.

November is the ninth month (after March) and is a lucky month which is almost free of religious obligation.

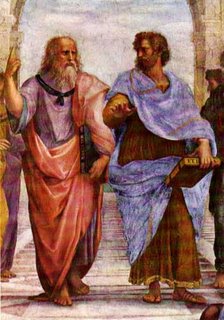

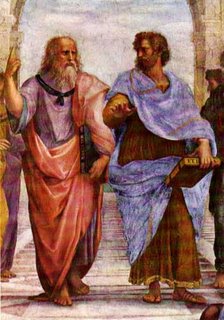

St Plato

The Macedonians watch the weather at sunset on the day of St. Plato (also called St. Plane-tree) carefully for it predicts the weather through Advent. In fact, it is said that Tsar Nicholas used the information gained from this weather oracle to predict the defeat of Napoleon as he marched towards Russia.

Plato (Platon, "the broad shouldered") was born at Athens in 428 or 427 B.C. He came of an aristocratic and wealthy family, although some writers represented him as having felt the stress of poverty. Doubtless he profited by the educational facilities afforded young men of his class at Athens. When about twenty years old he met Socrates, and the intercourse, which lasted eight or ten years, between master and pupil was the decisive influence in Plato's philosophical career. Before meeting Socrates he had, very likely, developed an interest in the earlier philosophers, and in schemes for the betterment of political conditions at Athens. At an early age he devoted himself to poetry. All these interests, however, were absorbed in the pursuit of wisdom to which, under the guidance of Socrates, he ardently devoted himself. After the death of Socrates he joined a group of the Socratic disciples gathered at Megara under the leadership of Euclid. Later he travelled in Egypt, Magna Graecia, and Sicily. His profit from these journeys has been exagerrated by some biographers. There can, however, be no doubt that in Italy he studied the doctrines of the Pythagoreans. His three journeys to Sicily were, apparently, to influence the older and younger Dionysius in favor of his ideal system of government. But in this he failed, incurring the enmity of the two rulers, was cast into prison, and sold as a slave. Ransomed by a friend, he returned to his school of philosophy at Athens. This differed from the Socratic School in many respects. It had a definite location in the groves near the gymnasium of Academus, its tone was more refined, more attention was given to literary form, and there was less indulgence in the odd, and even vulgar method of illustration which characterized the Socratic manner of exposition. After his return from his third journey to Sicily, he devoted himself unremittingly to writing and teaching until his eightieth year, when, as Cicero tells us, he died in the midst of his intellectual labors.